This week in North Philly Notes, Alana Lee Glaser, author of Solidarity & Care, writes about how her days as a labor activist informed her new book.

What is solidarity? What do we—as members of a society—owe one another? How might we effectively uphold and institutionalize our mutual obligations? These questions have animated my own activism and scholarship since I was an undergraduate student turned labor activist two decades ago. More recently, these same questions motivated me to write a book for undergraduate students that I hope might inspire them to solidarity action themselves.

During my first year as an undergraduate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, I, along with ten or so other students, staged a sit-in in the Chancellor’s historic South Building office on UNC’s central campus to protest the sweatshop labor behind the manufacture of the university’s licensed apparel. Months earlier, on a lark, I had attended a small meeting of anti-sweatshop activists. Over the course of those few months, I had what I now recognize as a full-scale world-view revolution. I entered college with an esteem for volunteerism and letter-writing campaigns (both of which I continue to endorse) and before my first year ended, I was a self-proclaimed labor activist and student radical. To contextualize, let me add that this all occurred in 1998, before historical hindsight would allow me to place my consciousness within broader anti-neoliberal globalization movements that united “Teamsters and turtles” in Seattle and countless others in global mass demonstrations against the anti-labor, free-trade policies of the World Trade Organization, IMF, and World Bank. Virtually all my subsequent endeavors have built upon the foundational experiences of student-labor solidarity that took place throughout my undergraduate career, leading me to Domestic Workers United, the organization of immigrant women domestic worker activists that is the subject of my book, Solidarity & Care.

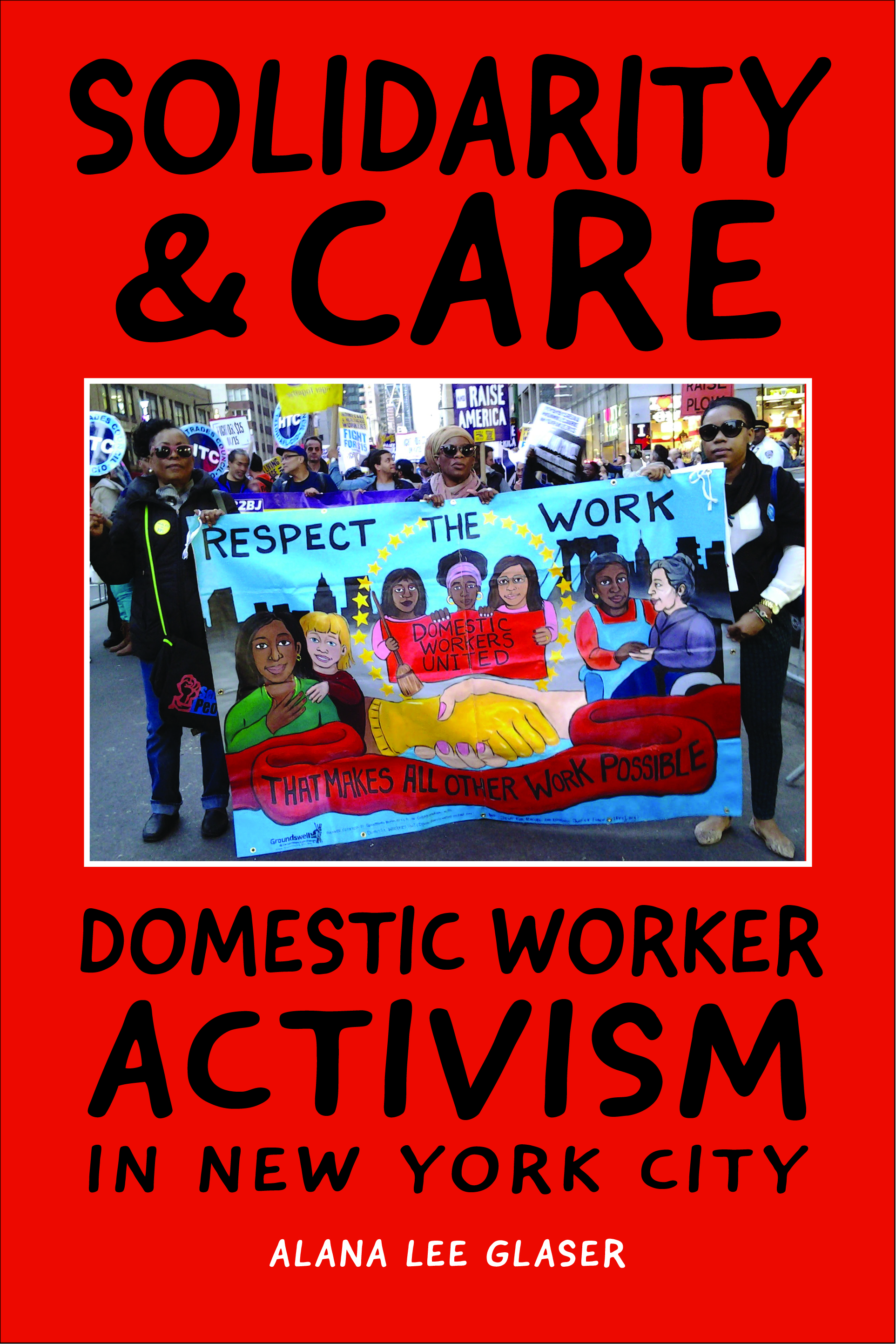

Solidarity & Care addresses these questions of solidarity, mutual aide, and activism through an accessible ethnographic description of Domestic Workers United’s decade-long fight to establish workplace protections in New York and the ramifications of this legislation in the ten years since it passed. Historically, U.S. labor laws have excluded care work performed in the home—housekeeping, childcare, and elder care—from labor law protections, leaving the women who work in this highly personalized, low-wage sector vulnerable to wage theft, harassment, abrupt termination, and abuse. In summer 2010, New York State passed the Domestic Worker Bill of Rights, the nation’s first-ever legislation granting formal protections to in-home workers.

Solidarity & Care chronicles the laboring lives and activist endeavors of immigrant women care workers across New York’s five boroughs, as they manage the implications of the new law in their workplaces, transnational communities, and political organizations. The introduction of the Domestic Worker Bill of Rights hasn’t attenuated many of the issues with which childcare providers, housecleaners, and home health aides contend on a regular basis—frequent termination, employer inconsideration, long hours, dismally low pay, mistreatment, and lack of control over their own labor. Solidarity & Care describes how care work positions exemplify increasing worker insecurity across industries—wrought by neoliberal economic policy and employer efforts to reduce wages and eliminate worker benefits through overseas outsourcing where possible and through casualization, deskilling, and fragmentation here in the United States. In this way, the book invites undergraduate students, many already working in low waged labor sectors themselves, to contextualize their own labor and to consider their experiences and interests in common with domestic workers.

By foregrounding the activist successes and setbacks of primarily Caribbean, Latina, and African women care workers, Solidarity & Care showcases how intersectional labor organizing and solidarity can effectively protect workers in this and other industries. It centers the voices and experiences of immigrant women workers through their oral histories, vibrant accounts of their roles in protest actions, and their own analyses of the overlapping oppressions they face as women of color, immigrants, and low-wage workers in New York City. Just as I was drawn to understand the historic and political circumstances during which I protested sweatshops by “sitting-in” as a an undergraduate, my hope is that Solidarity & Care will be an approachable invitation to undergraduates, and even the broader public, to reflect on their own political-economic position and to stand in solidarity with immigrant women workers, like the members of Domestic Workers United, and workers across the U.S. labor movement.

Filed under: american studies, civil rights, Disability Studies, economics/business, ethics, gender studies, health, History, immigration, Labor Studies, Latin American studies, latinos, law & criminology, political science, race and ethnicity, racism, sociology, Urban Studies, women's studies | Tagged: Actvism, African, demonstations, domestic workers, Domestic Workers United, immigrants, labor, labor movement, Latin American/Caribbean Studies, neoliberalsm, new york city, protest, race, radicalism, solidarity, U.S.labor laws, women, workplace protections | Leave a comment »